They say diversity is a thief, stealing the rightful place of the qualified, handing it over to those marked by race or sex who have not earned the crown. They dream of a pure meritocracy, a world where the smartest, the sharpest, the most capable rise to the top. And yet, I wonder, as I have wondered all my life, what is this thing called merit, and who dares to weigh it?

There is a dangerous innocence in America’s insistence on meritocracy. It is an innocence that pretends that merit is an objective measure, that talent and hard work alone govern who ascends and who remains, perpetually, in the shadows. It is this same innocence that allows the powerful to declare that diversity initiatives are antithetical to merit.

Let us consider, for a moment, what a true meritocracy might look like. If we believed, truly believed, that raw intellectual capability should be the sole arbiter of power and position, we would see a radically different world. Our boardrooms would be filled with those blessed (or cursed) with minds that can calculate pi to a thousand digits, who can recall every word they’ve ever read, who can see patterns in chaos that escape the rest of us. Our governments and schools would be run by those who score highest on IQ tests, the polymaths, the ones who unravel complex problems in the time it takes most of us to tie our shoes. We would see more industry leaders who are on the autism spectrum and more elected officials whose social graces might falter but whose minds sing with brilliance.

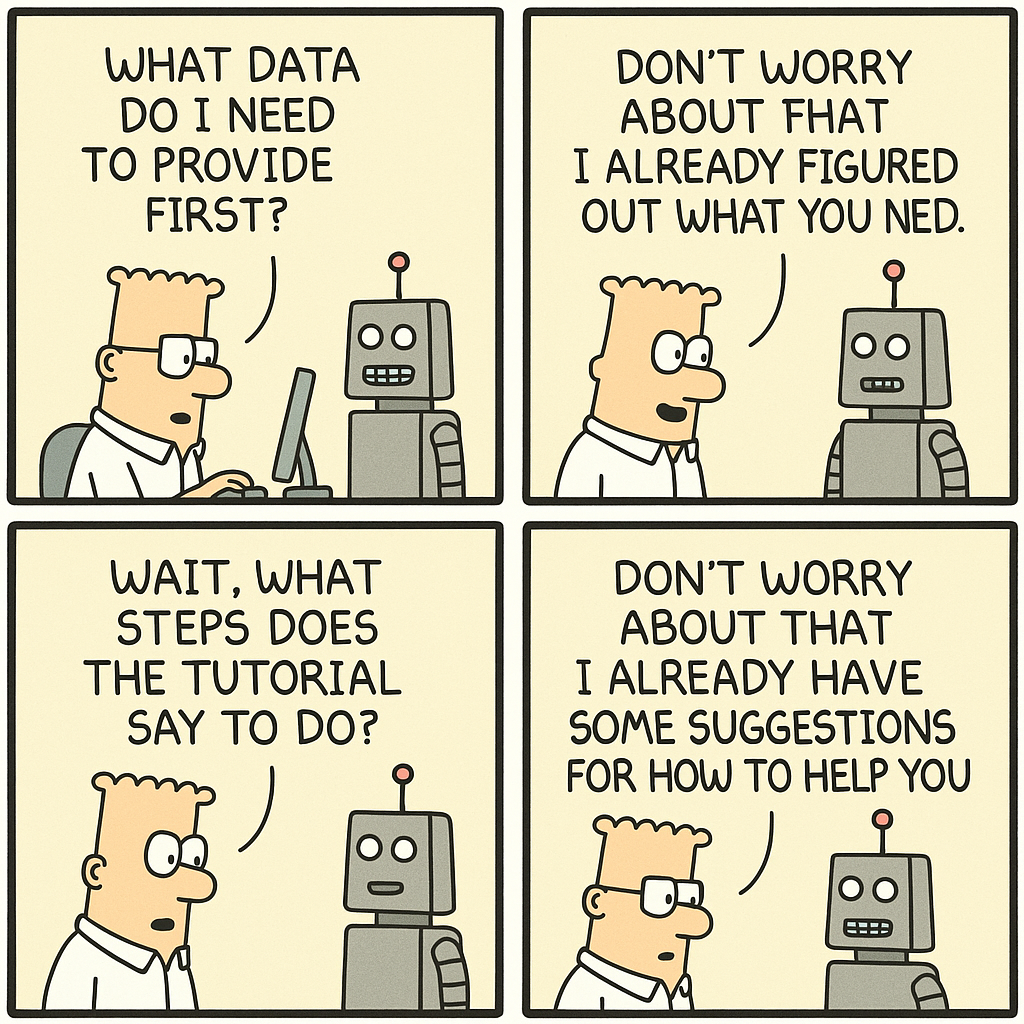

But look around you, America. Look at the faces in the C-suites, in the Senate chambers, in the ivory towers. Do you see them there? No, you do not. And why not? Because merit, as we live it, is not the clean, shining thing we pretend it to be. It is not a matter of raw intelligence or unblemished skill. It is a dance, a game of smiles and handshakes, of networks and nods, of being liked, and of being known.

Consider this: the man who runs the company, does he sit there because he scored highest on some grand exam of the mind? Or does he sit there because he went to the right school, knew the right people, played golf with the right crowd? The proof is in the pudding. A study from Harvard, that bastion of merit itself, tells us that 43% of its white students admitted between 2009 and 2014 were legacies, athletes, or children of donors and faculty—categories where intelligence alone does not punch the ticket. And what of the corporate world? A report from McKinsey shows that 70% of senior executives found their jobs through personal networks, not through some blind audition of talent.

Merit, it seems, wears a suit tailored by popularity, stitched with the thread of privilege.

If merit is a social game, then what of those who were never invited to play? Consider the young Black woman who graduates top of her class from a public high school in Detroit. She has never been invited to a country club where deals are made over golf. Her parents couldn’t afford to send her to the private schools where future CEOs form their first alliances. Her brilliant mind, her determination, her work ethic – these are not enough in a world where “merit” includes knowing which fork to use at a business dinner, which jokes to laugh at, which cultural references to drop in casual conversation.

What of the Latina, whose parents worked the fields while she studied by lamplight, but who never learned the secret handshake of the elite? What of the woman, told her voice is too shrill, her ambition too unseemly, her network too thin? What of the LGBTQ soul, who spent their youth hiding who they are, while others built the connections that would carry them to power? These are the ones who, through no fault of their own, inherit not opportunity but exclusion—not because they lack merit, but because merit, as we have built it, demands a currency they were never given.

The data bears this out. A 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research revealed that children from the wealthiest 1% are 77 times more likely to attend elite universities than those from the bottom 20%. This is not because wealth begets brilliance but because it begets opportunity. It buys tutoring, buys internships, buys introductions. It buys, in essence, merit.

A study by the Harvard Business Review found that 85% of jobs are filled through networking. Another study by LinkedIn showed that employees referred by other employees are 15 times more likely to be hired than applicants from job boards. Merit, it seems, has a lot to do with who you know, and who knows you.

The Economic Policy Institute tells us that Black college graduates are twice as likely to be unemployed as their white peers, even with the same degrees, the same “merit.”

Women, says the National Women’s Law Center, hold just 8.8% of CEO positions in the Fortune 500, though they are half the population—can we believe they are simply less meritorious?

The Williams Institute finds that LGBTQ workers earn less and face higher rates of discrimination, their talents buried beneath the weight of bias.

These are not failures of ability, but failures of access—of networks denied, of doors locked, of social cues misread or never taught.

To demand merit alone is to ignore how merit has been shaped, warped, and wielded by those who already hold the keys. To dismiss diversity as a crutch is to pretend that the playing field was ever level, that the game was never rigged.

And so, I ask you, America, is this meritocracy you defend so fiercely really what it claims to be?

Merit, it turns out, is not merely a function of intelligence or skill. It is also an equation of social grace, of being liked, of navigating the invisible networks of power. It is knowing which hand to shake and when, which jokes to laugh at, and which rooms to linger in long after the formal meeting has ended. It is having the ease of access that comes with wealth, the unspoken mentorship that comes with privilege, and the safety net that allows one to take risks without fearing the abyss.

If you are Black, Latino, a woman, LGBTQ, or part of any marginalized group, you are often shut out from these networks of power. You do not have the same uncles with corner offices or the same friends with venture capital firms. Your margin for error is razor-thin, and your every misstep is not a lesson but a liability. What is passed off as meritocracy, then, is merely the perpetuation of existing power structures. The same doors open for the same people, generation after generation, while the rest of us are told to pull ourselves up by bootstraps we were never given.

The push against diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives under the guise of preserving meritocracy is not about preserving fairness; it is about preserving power. It is about ensuring that the gatekeepers of society remain the same, that the story of who deserves what remains unchanged.

Diversity is not the antithesis of merit but its necessary corrective. It is the recognition that talent is not the sole property of the privileged, that brilliance can emerge from corners where opportunity seldom knocks.

To build a true meritocracy, we must first acknowledge the lie at the heart of the current one.

We must recognize that opportunity, not merely ability, has always dictated success. Only then can we begin to craft a society where merit is measured not by proximity to power but by the strength of one’s mind and the depth of one’s character. Only then can we live up to the promise we so often make, that in this land, what you achieve might finally depend on what you, and not your circumstances, can truly do.

I say this not in despair, but in hope—hope that we might see the fire of this truth and let it burn away our illusions. For if we truly want merit, we must reckon with what it has become, and we must build anew a system where the brilliant, the driven, the worthy can stand tall, not because of who they know, but because of what they are. Until then, the cry for merit alone is but a whisper of the past, a plea to keep the powerful in their place, and the rest of us in ours.